The Disappearance

Firingi’s heart was heavy. It had been five days since Babulal hadn’t come home. Babulal was his only son. When he left, he said he was going to a party meeting — he was supposed to return that same night. His parents waited up all night, but Babulal never came back. After two days of waiting, Firingi lost patience. Every time his mother called, the phone only repeated in a mechanical voice — “The number you have dialed is switched off.”

Unable to stay still, Firingi stopped working and began making rounds to the nearby police station.

A Son Feared and Respected

He knew his son was no saint. Babulal had spent nights behind the bars more than once. These days, he mingled with big political leaders. The police didn’t touch him, and the local people feared him. Sometimes the police would summon him, give a warning, but Babulal never cared. He wasn’t the kind to be scared.

He’d puff up his collar, chew his betel nut, snap his fingers, and boast —

“It’s our money that feeds the fancy habits of these policemen. Without us Babulals, their show would collapse. Their job is to say ‘no,’ but that doesn’t mean I’ve got to listen. If we go down, the leaders will be ripped apart by crows and vultures. We’re the poles that hold up their platforms.”

And he would burst into a wide, toothy grin — his betel-stained teeth flashing.

No one dared argue with him, but each time Firingi heard such words from his son, his heart trembled. We are men of the law, he’d think, and you’re a dom — a cremator’s son. You can’t fight the world with strength alone.

To which Babulal would calmly reply,

“Who told you I fight only with muscle, father? You need brains. In this age, brains are everything. That’s why everyone fears me — not because of strength, but because of wit. Otherwise, I’d be lying with the corpses in the morgue.”

His mother would shudder at those words. “Stop, my son,” she’d plead. “Don’t speak of such things.”

And Babulal would laugh so loudly the whole house seemed to shake.

The Dom’s Trade

Firingi worked as a dom at the Dum Dum Municipal Hospital — as his father once had. From his father he had learned how to slice open cold, stiff corpses and display their organs before the doctors, how to stitch them back neatly, and finally hand them over to the waiting families — with a discreet tip at the end.

He had been cutting bodies since his youth. The doctors, respectable men, never touched the bodies themselves. They only noted down what Firingi pointed out.

His experience was no less than theirs. He had to observe closely, understand deeply — one wrong post-mortem report could let a criminal slip through the cracks of the law. So Firingi did his work with care.

At first, the work made him nauseous. Now, even the stench of decay no longer bothered him; in fact, he had grown fond of it. Still, before stepping into the morgue, he always gulped down a few swigs of raw, burning liquor. Whether chullu or something stronger, it steadied his hands.

Though he followed his father’s trade, Babulal despised it.

“You’ve got the build of a sahib,” he’d tease, “and yet you’ve spent your whole life cutting up corpses. You could’ve made a name for yourself in a theatre troupe!”

It wasn’t the first time Firingi had heard that. His wife once said the same. But he always replied,

“I was born a dom’s son. If my forefathers didn’t mind, why should I? And if someone does, they’re free to stay away from me.”

After that, his wife never brought it up again.

Still, he often wondered why everyone called him Firingi — “the foreigner.” He once had another name, but from childhood everyone had called him that, until it became his identity. He didn’t even look like a dom’s son — more like a lost Englishman. People whispered, “Of course, he’s a Firingi by blood.”

Rumor had it his mother once worked as a maid for an Anglo doctor. His father never cared for gossip. Firingi was his own. His grandfather had been a cremator at Nimtala Ghat — a fearsome man whose very photo made people shudder. Babulal would salute that photo and say, “Now that’s what a warrior looks like!”

Waiting at the Police Station

For two days Firingi didn’t show up at the morgue. The hospital sent people to his home — three bodies were rotting, spreading a foul stench across the neighborhood. Families waiting for the bodies were furious, shouting at the hospital authorities.

But Firingi was unmoved. Since dawn he’d been sitting at the police station. Everyone there knew him, and the sub-inspector sent him a cup of tea. He wasn’t sure if the courtesy was for being Babulal’s father or for being the morgue’s dom.

He sat on a wooden bench in the veranda, slippers off, legs folded up. His face was vacant, his head drooped to his chest. He’d been sitting like that for hours, mosquitoes feeding freely. He wanted to light a bidi, reached into his pocket — and then stared at his hands. How many bodies had these hands dissected? Young, old, murdered, suicidal — whole, mutilated, rotten. He had grown used to it all. Yet whenever a corpse the age of his son came in, his heart twisted. That’s why he couldn’t work without a drink.

The inspector called for him. He rose and stood before the desk, anxiety burning in his eyes.

“Has Babulal come home?” the inspector asked. “Any call?”

Firingi shook his head. “No.”

The inspector glanced up briefly — Firingi’s once fair face had turned sallow. His sleepless nights and worry were written all over him.

“I want to file a missing report,” Firingi said, leaning forward. “It’s already late. Please, find my son.” His voice broke. He gripped the officer’s hand. “Please, sahib, bring my Babulal back.”

The officer averted his eyes, uncomfortable. “Go back to the morgue for now,” he said gently. “There’s a backlog of bodies. Once your report’s filed, we’ll start the process. We’ll let you know if we find anything. You understand, there are rules.”

Back to Work

Two days later, Firingi returned to the morgue — silent and heavy, like the sky before a storm. He had been drinking since dawn. When the waiting families saw him, one man shouted,

“Of course he doesn’t care — they’re not his people. If they were his own, he’d know our pain.”

Firingi flared up, eyes blazing. The doctor gestured for calm, and he swallowed his rage. But it seethed inside. He threw himself into work — tearing clothes off the bodies, clenching his jaw, cutting with a fury that frightened even the doctor. He worked like a mad bull. Only after a scolding did he steady himself — and took another swig.

Then came a new body — wrapped in green plastic, foul-smelling, half-decomposed.

“Found in muddy water,” the policeman said. “Animals took the head. Clean it up for the autopsy.”

Firingi dropped his knife. “Not today,” he said hoarsely.

“That won’t do, Firingi. Inspector’s orders. It’s a murder case. If we delay, the marks will vanish.”

“How will you identify a man without his head?”

“They’re still searching for it,” the officer replied.

Firingi’s eyes burned. “Have your men searched for my Babulal?”

“Your boy’s fine,” the officer said lightly. “Maybe got stuck somewhere. Young blood, you know. Probably out having fun. Get him married soon, that’ll fix him.”

That did it. Firingi roared, “You think it’s a joke? Because I’m a dom, I’m not human? You think I don’t have a heart? Touch me, and I swear I’ll grab your gun and shoot myself. That’s my last word.”

“Alright, alright, calm down,” said the officer. “Let’s finish this first. Then we’ll look.”

He took another gulp from his bottle and went back to work. Finished stitching the third body. The doctor offered him a cigarette.

“Cool your head,” he said. “Skip the next one. The morgue’s hell today.”

Firingi gave a twisted smile. “The morgue is hell, and I’m its god of death. But if we don’t find the head, who’ll take the body? It’ll rot here.”

“That’s for the police to decide. Go check the fourth one.”

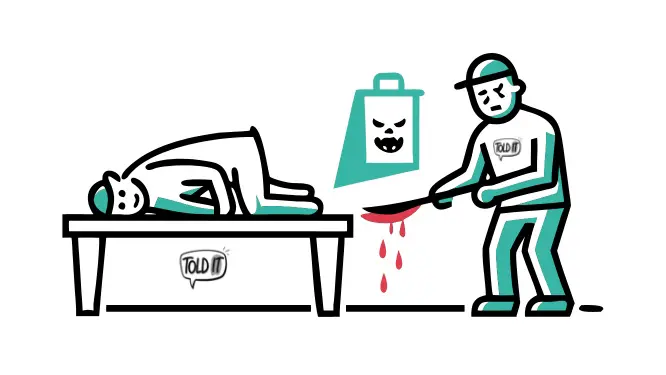

The Final Body

He stubbed the cigarette out on the floor, tightened his jaw, and walked to the last body. He dragged it into position, sliced open the bindings, and ripped away the plastic. A headless corpse, caked with blackened blood and mud. It was nothing new to him. He fetched a bucket, poured water over it, washing off the grime — countless gashes across the flesh.

“Looks like a brutal murder,” said the doctor, his nose covered. “See if there’s anything to identify him.”

Firingi turned the body over — then froze. On the right arm, a silver talisman bound with black thread. Familiar. Too familiar.

He leaned closer, trembling. Maybe it was a mistake. He flipped the body again, searching — there, on the back, a birthmark.

With a strangled cry, he threw away the knife and clutched the body to his chest, screaming,

“Doctorbabu!”

The doctor jumped in alarm.

Just then, a police van pulled up outside the morgue. They carried in a plastic bag.

Inside was a severed head.

Firingi rushed forward, tore the bag from their hands, and pulled out the head — pressed it to his chest, and wailed,

“Babulal—!”